Starting with the work done by March and Simon (more on them here) researchers have developed a step-by-step model of the decision making process and the issues and problems that managers confront at each step. I will try to present that information in a more human way, through the use of a case study.

The making of a decision

Perhaps the best example would be the decision making process followed by Scott McNealy at a crucial point in Sun Microsystems’ history. He was one of the founders of Sun Microsystems and also acted as chairman of the board of directors until Sun was bought by Oracle in 2010.

In August 1985, McNealy, then CEO of Sun Microsystems, had to decide if he should go ahead with the launch of the new Carrera computer, scheduled for September 10. The date was chosen by Sun’s managers nine months earlier when the development plan was first proposed. McNealy had to make a decision: launch on 10th of September or postpone to a later date.

McNealy knew that if they were to successfully launch their product on the 10th of September they would need at least a month to prepare. Customers were waiting for the new product, and Sun wanted to be be the first to take advantage of Motorola’s new microprocessor (16-megahertz 68020). Capitalizing on this opportunity would give Sun an advantage over its main competitor Apollo.

Committing to the September launch could be risky as Motorola had some production problems and could not guarantee a steady supply, and the OS was not completely finished. If they were to launch on September 10, some of the early systems would ship using unfinished software and a less powerful microprocessor. They could later update the software and chip but the company’s reputation would suffer. On the other hand if they would not launch that they would have missed on important opportunity. Rumors in the industry were that Apollo was gearing for a new product launch in December.

Clearly McNealy had a very difficult decision to make. He had to decide quickly even though he didn’t have all the facts. For example he didn’t know if Sun would be able to solve the software issues; nor did he know if Apollo would launch a competing machine. Unfortunately he couldn’t wait to find these things out.

The smarts behind a good decision making process

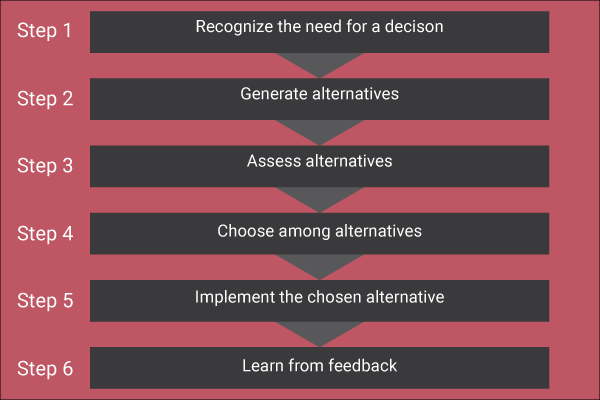

Managers who are required to make decisions with incomplete information face dilemmas similar to McNealy’s. Managers should make use of some kind of framework. Leaving important decisions on spur of the moment inspiration would not be recommended. Here are six steps for a good decision making process.

Recognize the Need for a Decision

This is the first step in the decision making process. Going back to our study case, McNealy recognized this and realized that a decision must be made quickly.

Some stimuli usually spark the realization that a decision must be made. These stimuli often become apparent because changes in the organizational environment result in new kinds of opportunities and threats. This happened at Sun Microsystems.

The launch date had been set when it seemed that Motorola chips would be available, but later doubt over supply and bugs in software can endanger Sun’s ability to meet that date.

Stimuli that spark decision making are as likely to result from the actions from inside an organization as they are from changes in the external environment. An organization possesses a set of skills, competencies, and resources in its employees and departments. Managers who pursue opportunities to use these competencies create the need to make decisions. Managers thus can be proactive or reactive in recognizing the need to make a decision, but the important issue is that they must this need and respond in a timely and appropriate way.

Generate Alternatives

Having recognized the need to make a decision, a manager must generate a set of alternative solutions to adopt in response to the opportunity or threat.

Experts often cite failure to adequately generate and consider alternatives as one reason why managers make bad decisions. For Sun the alternatives seemed clear enough: launch on September 10 or delay until the product was 100% finished. However the alternatives are not always so obvious and clearly defined.

According to Peter Senge, we are trapped within our personal mental models, our ideas about what is important and how the world works. Managers may find it difficult to define creative alternative solutions due to the fact that they view the world from a single perspective. For many of us coming up with creative alternatives and taking advantage of certain opportunities may require we abandon our preexisting mind sets and adopt new ones, something that we may find difficult or just impossible to do.

The importance of getting managers to set aside their mental models of the world and generate creative alternatives is reflected in the growth of interest in the work of authors such as Peter Senge and Edward de Bono, who have popularized techniques for stimulating problem solving and creative thinking among managers.

Assess Alternatives

Once managers have generated a set of alternatives, they must evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of each one. The key to a good assessment of the alternatives is to define the opportunity or threat exactly and then specify the criteria that should influence the selection of alternatives for responding to the problem or opportunity.

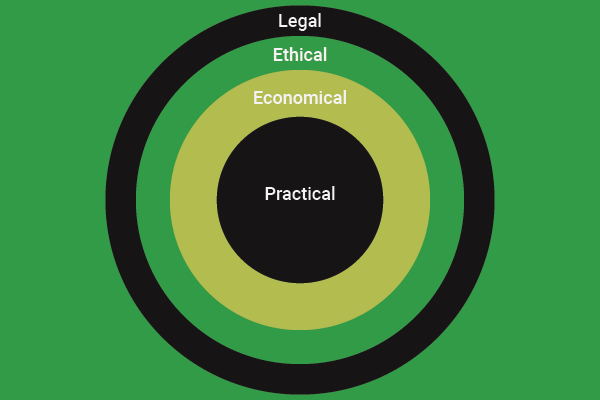

One reason for bad decisions is that managers often fail to specify the criteria that are important in reaching a decision. In general, successful managers use four criteria to evaluate the pros and cons of alternative courses of action.

Legality: Managers must make sure that a possible course of action will not violate any laws or government regulations.

Ethicalness: Managers must ensure that the course of action is ethical and will not unnecessarily harm any stakeholders. Many decisions managers make may help some organizational stakeholders and harm others. When examining alternative courses of action, managers need to be clear about the potential effects of their decisions.

Economic feasibility: Managers must decide whether the alternatives are economically feasible—that is, whether they can be accomplished given the organization’s performance goals. Typically managers perform a cost—benefit analysis of the various alternatives to determine which one will have the best net financial payoff.

Practicality: Managers must decide whether they have the capabilities and resources required to implement the alternative, and they must be sure the alternative will not threaten the attainment of other organizational goals. At first glance an alternative might seem economically superior to other alternatives; but if managers realize it is likely to threaten other important projects, they might decide it is not practical after all.

Often a manager must consider these four criteria simultaneously during the decision making process.

McNealy framed the problem at hand quite well. The question was go ahead with the September 10 launch date or postpone. The two main criteria that were influencing his choice:

- the need to ship a machine that was as “complete” as possible (practicality),

- and the need to beat Apollo to market with a new workstation (economic feasibility).

These two conflicted. The first suggested that the launch should be delayed; the second, that the launch should go ahead. McNealy’s actual choice was based on the relative importance that he assigned to these two criteria during the decision making process. In fact, Sun went ahead and launched the product on September 10, which suggests that McNealy thought the need to beat Apollo to market was the more important criterion.

Choose among Alternatives

Once the alternative solutions has been evaluated, the next task is to rank the alternatives (using the criteria discussed above) and make a decision. When ranking alternatives, managers must be sure all the information available is presented on the problem or issue at hand.

As the Sun study case indicates, identifying all relevant information for a decision does not mean the manager has complete information; in most cases, information is incomplete. Perhaps more serious than the existence of incomplete information is the often documented tendency of managers to ignore critical information, even when it is available.

Implement the Chosen Alternative

Once a decision has been made and an alternative has been selected, it must be implemented, and many subsequent and related decisions must be made. After a course of action has been decided thousands of subsequent decisions are necessary to implement it.

Although the need to make subsequent decisions to implement the chosen course of action may seem obvious, many managers make a decision and then fail to act on it. This is the same as not making a decision at all. To ensure that a decision is implemented:

- top managers must assign to middle managers the responsibility for making the follow-up decisions necessary to achieve the goal

- they must give middle managers sufficient resources to achieve the goal

- they must hold the middle managers accountable for their performance

- if the middle managers succeed in implementing the decision, they should be rewarded

- if they fail, they should be subject to sanctions.

Learn from Feedback

The final step in the decision making process is learning from feedback. Effective managers always conduct a retrospective analysis to see what they can learn from past successes or failures. Managers who do not evaluate the results of their decisions do not learn from experience; instead they stagnate and are likely to make the same mistakes again and again. To avoid this problem, managers must establish a formal procedure with which they can learn from the results of past decisions. The procedure should include these steps:

- compare what actually happened to what was expected to happen as a result of the decision.

- explore why any expectations for the decision were not met.

- derive guidelines that will help in future decision making.

Managers who always strive to learn from past mistakes and successes are likely to continuously improve the decisions they make. A significant amount of learning can take place when the outcomes of decisions are evaluated, and this assessment can produce enormous benefits.

I’ll leave you with this: the decision making process in Japanese firms is typically done in a group, which can take too much time and cause problems, as Toyota found out in early 2010.